An image of Rosie the Riveter that appeared in a 1943 issue

of the magazine Hygeia (Image Credit: American Medical Association)

WWII spurred unprecedented change, as well as new challenges, in America. Defense industry jobs created major population shifts to industrial cities, causing housing shortages and conflicts between races. The military’s need for food and other supplies resulted in rationing and scrap drives; and the need for millions of women workers during WWII permanently altered society’s ideas about child care and, at least for the duration of the war, the government’s role in supporting this valuable assistance to families nationwide.

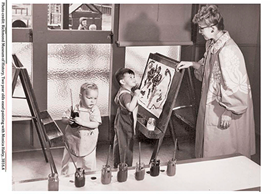

Women workers arriving at Kaiser Shipyard’s Child Care Center

At the beginning of WWII, government officials in charge of increasing the depleted workforce agreed that women with children were needed at home and wouldn’t target this group of women unless necessary. But by late 1942 the need for additional workers, especially in defense plants, was acute. The Office of War Information (OWI) and other agencies, which had previously induced married women to work, began a propaganda campaign to now get women with children into the workforce. American mothers, most who had husbands serving in the military or already working in the defense industry, were persuaded through the OWI’s print, radio, and other promotions, that it was their patriotic duty to leave their children and go to work. But as women began to answer Uncle Sam’s call it quickly became apparent that their success created a monumental problem: what to do with Rosie’s children?

With so many families relocating to industrial cities for work, many working mom’s had no relatives or friends nearby to care for their children. Horror stories of children left locked in cars or home alone began to circulate. Defense companies and other employers also complained about working mother’s absenteeism and losing their newly trained female workers who quit due to lack of child care. As author G.G. Wetherill observed in 1943, “The hand that holds the pneumatic riveter, cannot rock the cradle at the same time. Something had to be done.”

In 1940 the government had passed the Lanham Act, which was designed to assist communities with water, housing, schools, and other facilities needs related to war industry and growth. Under this Act, between August 1943 and February 1946, the federal government granted $52 million for child care (the equivalent of over $1 Billion today). It was the first federally subsided child care. This program was offered in every state except New Mexico. Funded by both federal and local money, over 3,000 child care centers were created, which by the War’s end had served between 500,000 and 600,000 children.

At first working moms and dads were apprehensive about leaving their children at these centers. Parents who normally would have had nearby relatives or neighbors help out, were uneasy about the idea of strangers helping to care for their young children. The concept of organized child care centers was something relatively new and the term “Day Care” was actually coined during this period.

Although the services at each center varied by community, each one provided the children with meals, beds or cots for sleeping, educational programs that ranged from lessons in reading, music and art, to the need for cleanliness and proper eating. Centers also offered odd hours to accommodate their mother’s work schedule and many even offered prepared meals to take home, a blessing after a long shift at work. The average cost was .50 a day (about $8.00 in today’s money); a real bargain to mom’s working 12-hours a day, six days a week.

Although the services at each center varied by community, each one provided the children with meals, beds or cots for sleeping, educational programs that ranged from lessons in reading, music and art, to the need for cleanliness and proper eating. Centers also offered odd hours to accommodate their mother’s work schedule and many even offered prepared meals to take home, a blessing after a long shift at work. The average cost was .50 a day (about $8.00 in today’s money); a real bargain to mom’s working 12-hours a day, six days a week.

Some companies used child care centers to their advantage and help create such outstanding facilities that morale and production levels increased because of working mom’s confidence in their child’s development and safety at these centers. Kaiser, a west coast ship building company, helped create 2 centers at their Portland, Oregon facilities. Their Child Service Department assured working mother’s “…the children will have an opportunity to live wholesome, happy lives.” Kaiser’s facility was opened 24 hours, seven days a week, and included a curriculum created by early childhood experts, an infirmary in case a child became ill, and offered three meals a day. As a result, Kaiser’s production levels were some of the highest throughout WWII.

Although these centers only serviced approximately 10% of the children in need, when the cancellation of the program was announced the government agency received thousands of letters, wires, and postcards and 3,647 signed a petition for additional funding. Unfortunately, after the immediate war-time need for government involvement in child care was over, so was the government’s desire to continuing assisting families in child care.

Fortunately for many Rosebuds and Rivets (the children of Rosies), who were able to participate in this federal experiment in child care, their reminiscences of WWII include the memories of their time at these centers, and for Rosie moms, they provided comfort, knowing that their children were well cared for while they did their part to help win the war.