Review by Jeannette Gutierrez, originally published on the Diary of a Rosie blog. (Click here for original article.)

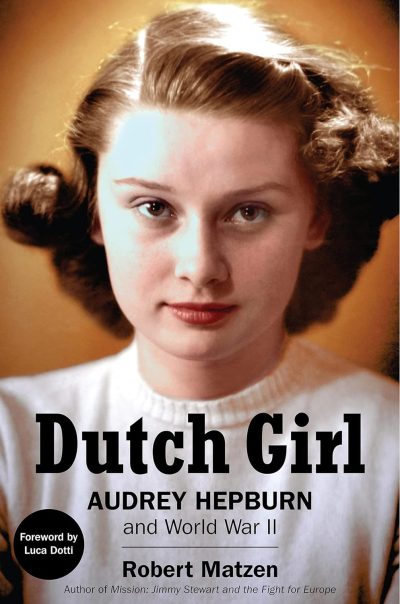

Published in 2019, the excellent book, Dutch Girl: Audrey Hepburn and WWII by Robert Matzen, is a painstakingly researched, heartbreaking, and ultimately uplifting account of the Hollywood star’s formative years in the Netherlands under Nazi occupation during WWII. Read this amazing book for the full story of Ms. Hepburn’s experience as a girl in the war torn Netherlands.

(Click here for Amazon link)

Pre-war in England and Arnhem

Audrey Hepburn-Ruston was born in Belgium to a Dutch mother and English father. She was educated in England and moved to Arnhem in the Netherlands in 1939 after her parents divorced. With full-scale war in Europe about to break out, the 10-year-old flew alone to Amsterdam on one of the last passenger aircraft to leave England for the continent. Audrey’s mom felt Audrey and her brothers would be safer with her in the neutral Netherlands.

A shy and artistic girl, Audrey (called Adriaantje by her Dutch relatives) settled into life in Arnhem with her mother Baroness Ella van Heemstra’s extended family. Although titled Dutch aristocracy, the van Heemstra family was not particularly wealthy.

In Arnhem, young Audrey fell in love with ballet after seeing the legendary Margot Fonteyn perform there with a British dance troupe and would soon begin an intense study of the discipline. But first, the unthinkable happened. Germany invaded the Netherlands. Audrey’s no-nonsense mother Ella roused the just-turned-11-year-old on the morning of May 10, 1940 with the words, “Wake up. The war’s on.” Germany’s 6th Army swarmed into town and took control, beginning the 5-year ordeal that was Audrey’s adolescence.

A Heavy-handed Rule

Over the next years, the sensitive girl endured many hardships and witnessed many horrors. She saw persecution, beatings, and finally removal of the city’s Jews. She saw Jewish men and women, children and the aged, peering out from wagons and cattle cars at the train station.

Her beloved Uncle Otto, Count van Limburg Stirum, was relieved of his position as a public prosecutor when he refused to prosecute a drunk man for singing a song banned by the Nazis. Worse things were in store for Uncle Otto as the occupation wore on.

By the winter of 1941-1942, coal was scarce and food was rationed as most resources were being funneled to German troops fighting on the Eastern Front. While not yet starving— that would come later — the family’s nutrition was poor. Audrey’s teenaged brother went into hiding to avoid conscription into the German army by the Nazis.

In fact, many were in hiding in the Netherlands during the war years. Although the Germans considered the Dutch their Aryan cousins and expected a warm welcome, the Dutch did not return the sentiment and mounted an active resistance movement. This included sabotage, opportunistic killing of German soldiers, sheltering and aiding downed Allied flyers, and hiding an estimated 28,000 Jews as well as able-bodied Dutchmen who wished to avoid German forced-labor press gangs. These hidden people were called onderduikers (literally, under-divers).

In February 1941 in Amsterdam, Dutch citizens staged protests and strikes in response to the increasingly harsh treatment of Jews. Nevertheless, as the occupation progressed, Holland’s Jews gradually disappeared — taken away by the Nazis or gone into hiding. The Dutch became aware that their missing Jewish neighbors were being exterminated, and this awareness was another horror endured by young Audrey.

Uncle Otto’s Fate

In 1942 in Arnhem, the Nazis began to arrest some of the city’s leading citizens. Among these respected politicians, aristocrats, and businessmen were Audrey’s beloved Uncle Otto and two other members of her extended family. These men, 460 in all, were imprisoned and held by the Nazis as “death candidates” who could be killed in retaliation for the activities of the Dutch Resistance. On August 14, 1942, as a misdirected punishment for an act of railway sabotage, Audrey’s Uncle Otto, a cousin, and three other prominent Dutchmen were marched to a wooded area, forced to dig their own graves, and executed by the Nazis. They died bravely, with an oath of allegiance to their Queen and country on their lips.

Suspected Resistance sympathizers, when captured, were detained in a former bank building in downtown Arnhem that was devoted to their interrogation and torture. Many, including Audrey, experienced hearing their screams as they passed by.

Mother Ella and Fascism, Audrey and the Ballet

By this time, Audrey’s mother Ella — who along with Audrey’s English father had been a great admirer of fascism during the 1930s — had changed her mind about the Nazis.

While still married and living in England, the couple had travelled to Germany twice, along with notorious British fascists Sir Oswald Moseley and the Mitford sisters. Ella had even met the Fuhrer himself on one memorable occasion. In the first year of the German occupation of Arnhem, Ella had been friendly with German officers, who were frequent guests in her home. Meantime, Audrey’s distant and mercurial father, Joseph Hepburn-Ruston, was sitting out the war in Britain, imprisoned as a known fascist.

In Arnhem, Audrey, who studied ballet under a master ballerina at Arnhem’s Muziekschool, quickly became something of a young dance sensation. As the Germans took over and Nazified the arts in Arnhem, she and her troupe presented Nazi-approved ballets with occupying officers populating the front rows. Jewish musicians and dancers one by one disappeared, and by early 1944 the Nazis were requiring that performers become card-carrying members of the Nazi-sympathizing Dutch National Socialist Movement. This was anathema to the van Heemstras, including by now even mother Ella. So Audrey, who at this point in the occupation was also weakened by malnutrition, gave up rigorous formal ballet instruction and ceased performing at the Muziekschool.

The van Heemstras Join the Resistance

Mother Ella now became active in the Dutch Resistance, organizing clandestine music and dance performances for Resistance members and sympathizers, as both a way to raise money for their activities and to keep her talented daughter involved with dance. These illegal arts performances were called zwarte avonden (black evenings).

The van Heemstra family also got involved with the doctors at a nearby hospital, which served as the de facto local headquarters of the Resistance. The doctors would deliver messages and goods to resistance fighters under the guise of making house calls and delivering medicine. False papers were manufactured in the hospital’s offices. The hospital itself sheltered onderduikers, including nine Jews in a secret space in the attic.

Audrey began helping out at the hospital, including making some of these clandestine deliveries for the doctors. Several neighborhood youngsters were employed this way, and although they knew the dangers of what they were doing, they usually didn’t know exactly what they were delivering. On one memorable occasion Audrey, fluent in English, was sent to give supplies and escape instructions to a downed British airman hiding in a nearby forest. The flyer must have been surprised and delighted to hear the graceful teenager address him in perfect English. Spotted by a German patrol, resourceful Audrey pretended to be picking wildflowers, her true mission undetected.

All Hell Breaks Loose

In August, 1944 the fighting came closer to home as Allied bombers pounded the German airbase near Arnhem, causing civilian deaths and destruction in the town.

Meantime, in retaliation for another act of sabotage by the Resistance, the Nazis had set an execution date of September 17 for over 100 Dutchmen, without specifying who. The van Heemstras were terrified that Audrey’s grandfather and patriarch of the family, the elderly Baron van Heemstra, would be marked for death as Uncle Otto had been.

But in September 1944 the Allies launched Operation Market Garden, an ill-fated attempt to secure Dutch bridges in preparation for invading Allied ground troops. Among the targets was the Arnhem road bridge, the battle for which was immortalized in the 1977 movie, A Bridge Too Far.

Audrey and her neighbors awoke on the morning of the 17th to a sky filled with Allied aircraft, pounding German strongholds in and around the city. While citizens ran for shelter, the Germans sent bullets, flak and fighters into the air over the city, and the Battle of Arnhem began in earnest, with the air battle raging all morning. In the afternoon the all-clear siren sounded, and as the Dutch emerged from their homes and cellars to survey the damage and help stricken neighbors, they heard more planes approaching and were treated to the sight of thousands of parachutes descending on the fields outside of town. These were the 10,000 troops of a British 1st Airborne Division charged with capturing the Arnhem road bridge. Euphoria reigned with shouts of “Liberation!” as British paratroopers swarmed into town, but hopes were soon dashed as the Germans responded and fighting commenced.

The Dutch had no choice but to return to whatever shelter they could find and await the outcome of the battle, which lasted for days. The British “Tommies” who took up positions in homes and buildings around town were polite and apologetic. But as the battle raged, Tommies and civilians alike died under fire, and much of the city was destroyed. No amount of death and destruction – and there was plenty – could dim the enthusiasm the Dutch had for their would-be liberators, the brave and cheerful Tommies. Over the course of the next week, most of these men would die or be taken prisoner. One Dutch housewife buried over 50 fallen British in her garden. As the Allies lost the battle, the Dutch sheltered and hid many Tommies, who joined the ranks of the city’s onderduikers supported by the Resistance.

The Aftermath of Operation Market Garden

The battle for a bridge too far took a toll on the van Heemstra family. Located right next to the bridge, the school owned by Uncle Otto’s aunt, Cornelia Countess van Limburg Stirum, was destroyed and the elderly countess perished with it. A van Heemstra family home near the bridge, as well as Audrey’s beloved Muziekschool, ended up in ruins as well. And although the family and their current home survived the battle, they now had a fugitive British soldier lodged in the basement. The punishment for this, if discovered, was death for the entire family. With so many injured civilians (and hidden British) the nearby hospital was inundated and short of supplies. So Audrey and mother Ella now spent their days helping with the wounded and spent nights boiling used bandages.

The Germans began sending V1 rockets over the area, aimed at Allied positions in Belgium. The sound of these rockets signaled terror as many of them malfunctioned and dropped randomly over Arnhem, setting buildings aflame and killing civilians. Allied fighter planes now appeared regularly to strafe and bomb German equipment and troops flowing through town as the western battlefront moved nearer. Dutch civilians were regularly caught in the crossfire. Among Audrey’s many friends and neighbors who were casualties of the fighting was a woman killed while pushing her own and other neighborhood children into the safety of a building. After the women’s death, her young son found solace in Audrey’s company, coming to the hospital every day to sit with the gentle teenager, who loved children, while she rolled bandages.

The Hunger Winter Arrives

Thus the stage was set for the terrible “Hunger Winter” of 1944-1945. With supply trains cut off by battles raging outside of Holland’s borders, no food was getting in. What little food there was went to occupying German troops. Rations allotted to civilians consisted of hot water and one slice of bean bread per person for breakfast, and a soup made with a single potato for the whole family for lunch. When even these meager rations ran out, the Dutch scavenged the surrounding countryside for anything edible. They dug under the snow for the odd potato missed in last season’s harvest, and gathered crop dust off the harvesting machines. Imagine eating dust! They even dug up and ate tulip bulbs from their frozen gardens.

The van Heemstra household was no different, with Audrey’s mother and aunt slipping much of their rations to their elderly father the Baron, while Audrey herself tried to minimize her own consumption to nourish her mother and aunt. As hunger took its toll on all of them, Audrey could not sit for any length of time because her buttocks had withered away. An estimated 22,000 Dutch died of hunger that winter. Meantime, the war raged around them as Allied air attacks on the Arnhem area continued while German V1s fell and the Nazis terrorized the populace with reprisal executions and forced labor roundups. For the most part, the Dutch hunkered down in their basements and hoped their houses would still be still standing at the end of the day. One evening in March, Audrey’s aunt informed the starving family that they should just stay in bed the next day to conserve energy, as there was nothing to eat. Miraculously, a member of the Resistance appeared at the door that morning with butter, eggs, flour and meat obtained through Swedish aid efforts. The family ate their first real meal in many months and, again, Audrey survived.

Liberation!

Liberation finally came one morning in April, a couple weeks shy of Audrey’s 16th birthday. The shelling and shooting died down and finally stopped, and Dutch citizens emerged from their basements to the welcome sight of Canadian forces marching down the street. There was much celebration. The Dutch civilians produced champagne from secret hiding places, while the Canadians handed out cigarettes and chocolate. Audrey ate every piece offered, was sick to her stomach, then ate some more. She smoked her first cigarette, handed to her by an Allied soldier, starting a lifelong habit she could never shake: to Audrey, the smell of tobacco was the smell of liberation. Although the van Heemstras’ Tommy-in-the-basement had long since been handed off to the Resistance, one thing that surprised many Dutch that day were all of the onderduikers that emerged into the streets. Some were amazed to learn that Jews had been hiding right next door for years!

After the war, Audrey regained her strength and moved to London with her mother to continue her study of dance. Dance led to modeling and acting, and by the early 1950s Audrey was the international film star that we remember today.

And a Purpose-driven Life…

Medical experts will tell you that a childhood of extreme stress and privation does not make for a long life. Young Audrey’s health and metabolism were permanently affected by the war, and both of Audrey’s parents outlived her. She died way too soon, of cancer, in her early 60s. She didn’t talk much about her war experiences, and made light of her Dutch Resistance activities, saying she was just a child and there were many others who did braver and more important things. What the war, and her innate love of children, did leave her with was a huge compassion for the plight of children in war zones. She spent the last years of her life working for UNICEF to bring attention and aid to children in places like Ethiopia, Central America, and Somalia. Although she loved her mother and remained close to her all her life, those nearest to Audrey say that at some level she never forgave Ella for her early infatuation with Hitler and the evil that was fascism.

In the words of author Robert Matzen, “Audrey got the full wartime tour, soup to nuts. She witnessed executions. She saw body parts in the street after bombs tore up her neighborhood. She stemmed the bleeding of wounded soldiers and civilians until she too was covered in blood. She had guns pointed at her by Germans and Brits alike, and stood in the direct path of machine guns as they rattled away. Your Audrey Hepburn endured all that.”

I urge you to read this amazing book! Matzen did four years of research, made several trips to Holland, and spoke with survivors to paint a frighteningly realistic and detailed picture of life in a war zone and the living hell Audrey Hepburn, her family and fellow Dutch citizens endured. It’s inspiring to read how this exquisite and innocent young soul could witness such horrors and emerge a kinder, stronger and more beautiful person than ever.

Matzen says that he fell in love “after spending four years with Audrey,” and you will, too, after reading this book.

(Click here for Amazon link)