The Office of Civil Defense (OCD) was originally established under the President as part of the Office of Emergency Preparedness in May 1941. It was created to coordinate state and federal measures to protect citizens in case of war emergencies. The federal government sponsored public service announcements to promote participation in the drills and blackouts and make sure people knew what to do. These measures included posters and pamphlets, as well as training manuals that instructed citizens to have emergency supplies in case of an air raid. Necessary supplies included 50 feet of garden hose with a spray nozzle, 100 pounds of sand divided into four containers, three 3-gallon metal buckets (one with sand and two filled with water), a long-handled shovel with a square edge, a hoe or rake, an ax or hatchet, a ladder, leather gloves, and dark glasses.

Air raid drills were prescheduled as to not cause panic and announced in newspapers and radio broadcasts. While large cities erected huge sirens; New York City had 409 sirens, smaller towns might ring church bells to alert residents of a drill. Alarms normally sounded for 30 minutes until the drill was completed. Once the alarm was sounded a large squadron of volunteer air wardens drove around America’s roads and streets to ensure no light was visible. If a resident didn’t comply the air warden would approach the house or shout “Put out the lights!”

During drills, along with dousing lights, citizens were required to shut off appliances, disconnect electricity, turn off gas and water, and might include moving to a shelter or basement until the drill ended. Cars were required to pull over, turn off their vehicles, and find a shelter.

By early 1943 nearly 6 million patriotic men and women had volunteered as air raid wardens. Large cities like Detroit had more than 100,000 volunteer air wardens and auxiliary firefighters alone. Training for these volunteer positions required training in how to wear a gas mask, rescuing injured people, learning first aid, and putting fires out. One of the quirky propaganda pieces of the time was a 1942 song by Tony Pastor and his Orchestra “Obey Your Air Raid Warden,” which instructed listeners, “Don’t get in a huff/our aim today is to call their bluff. /Follow these rules and that is enough. /obey your air-raid warden.”

Schoolchildren were also required to practice air raid drills at school. Boys and girls lined up separately and marched to basements or hallways, gathered in assigned areas, and often instructed to bow their heads to protect them from debris in case the school was hit by a bomb. Duck and Cover under desks wasn’t initiated until the 1950s with the fear of nuclear war.

While air raid drills were an occasional disruption, blackouts were a nightly condition. Blackouts required residents to cover windows and doors with heavy drapes or other material to block out all light each night by 11pm. Street lights were extinguished and hoods covered the tops of traffic lights that are still made that way today. Automobile headlights were covered or used new lamps that had been approved by the War Department. These lights were designed by U.S. Army Engineers and mass-produced by General Electric and were equivalent to one-sixth of the light cast by a full moon on a clear night. This dim light could not be seen from the air and still allowed traffic to move at 12mph.

Businesses were required to turn off all signs and lights. Charles Lindbergh notes in his war time journal of a trip to New York City, “The entire city was dimmed out but some resourceful stores had screens hanging just inside the glass. You could see fairly well when looking directly but the screens shut off the light completely at an angle.” Factories that were running three shifts in order to produce needed war materials needed to keep their lights on without interruption. But these were considered prime targets for attack; so many companies installed huge window and door coverings to protect them from enemy attack.

The metal poles that run along the top of this hanger building at Ford’s Willow Run Bomber Plant in Ypsilanti, MI were designed to hang massive blackout curtains. Photo credit Debra Wake.

Although cities along the Atlantic coast resisted these safety measures that they thought interfered with tourism, Pacific coast residents took blackouts very seriously. On Dec. 8, 1941, the evening after the attack on Pearl Harbor a crowd of angry citizens gathered in downtown Seattle, Washington. Several stores had not extinguished their signs after closing for the day. Rioters took to the streets, smashed lit signs and dozens of windows, stopping occasionally to sing God Bless America, before continuing in their destruction. Police eventually arrested 7 people and dispersed the rest of the crowd.

No enemy attacks ever occurred by air but on June 21, 1942, a Japanese submarine surfaced near Fort Stevens, Oregon, and opened fire. The fort, not wanting to give away their exact location, did not return fire. A complete blackout was instituted for the surrounding town, and with no visible target the sub fired blindly for fifteen minutes before giving up. No one was injured and only the ball field at the base was damaged.

Although no plane spotter ever spotted a plane, the U.S. government considered the blackouts and air raid drills successful. There were naturally problems that occurred with these wartime safety measures. There were many false alarms and drills sometimes caused disruption to activities: in the summer of 1942 a drill caused the lights to go out in the middle of a ball game between Washington and Philadelphia at Griffith Field. There was also an increase in accidents and fatalities due to the demised vision of night driving. Crime and murder was also reported to have increased some locations due to increased darkness.

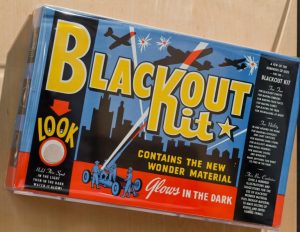

A lighter side to the nightly blackout requirements during WWII was a “Blackout Kit,” produced by the Vernon Company of Newton, Ohio. The kit included 5 rolls of Blackout material [luminous paper]; official Blackout test tube, “Voodoo Man” mask sheet, and a great instruction/ideas booklet. The elaborate instruction book was packed with info and great illustrations (traceable civil defense insignias, blackout party ideas, glow-in-the-dark novelties, etc.). This may have been designed to lighten the mood as well as entertain the children in the house during the dark times of war.

A lighter side to the nightly blackout requirements during WWII was a “Blackout Kit,” produced by the Vernon Company of Newton, Ohio. The kit included 5 rolls of Blackout material [luminous paper]; official Blackout test tube, “Voodoo Man” mask sheet, and a great instruction/ideas booklet. The elaborate instruction book was packed with info and great illustrations (traceable civil defense insignias, blackout party ideas, glow-in-the-dark novelties, etc.). This may have been designed to lighten the mood as well as entertain the children in the house during the dark times of war.

For approximately four years Americans at home did their part to keep the home front secure. Thank you to the millions of men and women who took on the additional wartime assignments as air wardens and other positions needed to maintain civil defense.