WWII dramatically changed society’s notion of what women were capable of as millions of women took on war-related jobs previously done by the men now in Service. Society’s perception of women’s abilities, as well as women’s own understanding of their value was especially true for African-American women. These “Black Rosies,” who had previously been at the bottom of the labor pecking order, finally got the opportunity to prove their worth and that they too, could do it!

You won’t find WWII era ads or recruitment posters encouraging black women to enter the factories, government offices, or ship yards, but approximately 600,000 African-American women did just that.

Despite their achievements, these black Rosie the Riveters still do not receive the same attention as their white counterparts. This maybe partially due to the fact that 44% of black women were already working in menial jobs outside the home before WWII, or that black women were the last one hired (after white males who had deferments, white women, and black men). So many black women did not get their jobs until the later part of the war.

In the recent documentary, “Invisible Warriors: African-American Women in World War II,” historian and film maker Gregory S. Cooke conducted dozens of interviews and explained how civil right workers, like Mary McLeod Bethune, as well as FDR’s own wife, Eleanor, applied pressure to President Roosevelt until he signed Executive Order #8802. This Order, which banned discrimination in Defense Industry hiring, finally opened the door for minorities. Many black women, who had previously been relegated to low-paying jobs, such as domestics, or worked as sharecroppers in the South, now found better paying jobs in war-related industries. Just like the white Rosies, they also traveled from all parts of the country to work in the industrial cities and towns that produced planes, ships, and other necessary goods for the war effort. But unlike their white counterparts, they also faced discrimination in housing and the new child care program was not available for African-American families. Black women were also excluded from joining established unions and were often given harder or more dangerous jobs.

These black Rosies included Tina Hill, whose story was captured in Rosie The Riveter Revisited. Tina was born and raised in Texas and attended the Negro Vocational College in Prairie View before going to work as a domestic at age 18. She later married and was living is Los Angles when her husband entered the Army during WWII. In Los Angles, the local Negro Victory Committee offered black women training and helped them secure employment in the defense industries. In 1943, after completing training, Tina went to work for North American Aircraft. Tina worked there as a riveter for 2 years before leaving on maternity just before V-J Day. Tina was one of the lucky women; she was later called back to work by North American Aircraft, where she worked for almost 40 years. Tina, as well as many other black women, was conscious of the historic role she played. She and other black workers had no doubt read and understood the War Worker’s Pledge:

“I shall never for a moment forget that thirteen million Negroes believe in me and depend on me…I am a soldier on the Home Front and I shall keep the faith.” The War Worker’s Pledge from WWII pamphlet, issued by the National Council of Negro Workers.

Black Rosies each have unique stories that help us to understand the significance of their wartime jobs. Each life shaped by their background, their experiences during the war years, and the changes these unique work opportunities made to their future. These jobs went a long way in helping create a new black middle-class. (This would also lead to new conflicts between the races and help ignite the civil rights movement, causing further struggles for African-American growing up in America.)

So while Tina had left Texas for the west coast and been able to secure permanent employment, other African-American Rosie’s lives were changed in other ways.

Photo permission from Clara Doutly

Clara (Hunter) Doutly was born and raised in Detroit. She did very well in school and was attending the predominately white Cass Technical High School when she left before graduating to work as a riveter at Briggs Manufacturing in Detroit. Clara helped to build the B-29 bombers. Clara says she was grateful to get the job and although she encountered racism, by both white males and females, at the Briggs factory, her mother had raised her to believe that she was as good as anyone else. Clara says she ignored the difficulties and just did her job. Clara says she worked 10 hour days, but in her free time she enjoyed going to Belle Isle Park, a 980 acre island park located in the middle of the Detroit River, with her friends.

Following the war Clara stayed in Detroit, married, and worked for Detroit Public Schools. She has spent her entire life in Detroit and in October 2021, while celebrating her 100th birthday, she received an honorary diploma on behalf of Cass Technical High School and the Detroit Public School District. Ford Motor Company also honored Clara with a bench on the east side of the Belle Isle Park, which was dedicated this month. Rosie Clara has appeared in Detroit’s Thanksgiving Day Parade and featured in National Geographic’s 75th Anniversary of the end of WWII commemoration. (Gleaned from personal interviews between 2017-2022 with Clara Doutly.)

Photo by National Parks

Another Detroit-born African-American Rosie, Betty (Charbonnet) Reid Soskin, has made it her job to share her own WWII experience as a Park Ranger at the Rosie the Riveter/WWII Home Front National Historical Park in Richmond, California.

Betty’s family had settled in Oakland, CA, where she married Mel Reid in 1943. After the US entered WWII, Betty began work as a file clerk for the Boilermaker’s A-36 union, her main job was filing the many change of address cards for the many workers who moved frequently. After the war, Betty and her husband founded Reid’s Records in Berkeley, which operated for 75 years.

Betty and Mel divorced in 1972 and Betty later married William Soskin, a psychology professor at the University of California, Berkley. Betty took over the management of Reid’s Records in 1978 and became a community activist. She later served as a field representative for two California State Assemblywomen, where she became involved with the planning for what would become the Rosie the Riveter/World War II Home Front National Historical Park in Richmond, CA.

At age 84 Betty went to work for the Park Service, leading public programs and sharing personal remembrances at the Historical Park she helped create. Betty has received many awards, including the Silver Medallion Award at the World War II Museum in New Orleans in 2016. In 2019 a film was produced by the Rosie the Riveter Trust, “No Time To Waste: The Urgent Mission of Betty Reid Soskin.” The documentary tells the story of Betty’s work with the Rosie the Riveter/WWII Home Front National Historic Park. On March 31, 2022 Betty retired from the Parks Service at the age of 100. She was the oldest National Park Ranger in service in the US.

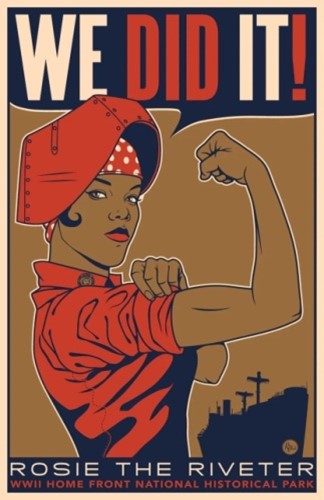

Ruth Wilson points to work of artist Regina Cooke, who reimagined Rosie the Riveter as a black women, using Ruth as her model. Photo credit 6abc Digital Staff.

World War II finally gave black women the opportunity to make a decent wage and help our nation save freedom, even when civil rights were not extended to them. Now we need to gather and preserve these stories of their courage and can do attitude, the true legacy of Rosie!

Ruth Wilson, who is featured in the Invisible Warriors documentary, began working as a domestic at age 13. During the war she moved to work in the laundry at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, but quit when her manager told her to work through her lunch time. Days later she received a letter from the government stating that she could not quit a job during the war, as they needed workers, so Ruth took a test and qualified to be trained as a sheet metal worker. After 6 weeks of training she went to work at the Navy Yards dry dock where she helped build the USS Valley Forge aircraft carrier. Ruth was sent home when the war ended but she never went back to being a domestic. After the war she went to work in a doctor’s office before getting a job in a factory making children’s coats. Ruth worked 30 years and was able to help provide a better future, and is a role model for her daughters, grand-daughters, and great-granddaughters. As she said in a recent TV interview, “We love this country as much as everyone else.” And her WWII experience taught her that “everyone is important.”

World War II finally gave black women the opportunity to make a decent wage and help our nation save freedom, even when civil rights were not extended to them. Now we need to gather and preserve these stories of their courage and can do attitude, the true legacy of Rosie!

Richmond Rosie Poster honoring WWII’s African-American women. Available from Rosie the Riveter Trust shop at rosietheriveter.org